In 2007, taking stock of the centenary of aeronautics in Germany, Helmuth Trischler and Kai-Uwe Schrogl concluded that aviators were vested with male attributes even more in Germany than in the United Kingdom and the United States.1 Perhaps the Nazi regime and its desire to create a new fascist man reinforced the place of young pilots in the discourse of modernity.2 Yet this emphasis on the aviator was common to Western nations in the early twentieth century.3 What about France, one of the first aeronautical nations in history?4 While the gender perspective has been embraced by the social sciences for several decades, they are still relatively absent from historical studies on aeronautics. The theme deserves to be explored in greater depth, as it appears that aviators are models of masculinity in a context of restructuring gender relations in the first half of the 20th century.5 Airmen seem to participate in the hegemonic masculinity theorised by Raewyn Connell, i.e. the masculinity that prevails in representations as well as in social relations.6 They thus form a relatively new normative figure before 1939, that is, a dominant representation that sends a set of injunctions to the rest of society, which mode can be defined as virility. The latter, which is relatively stable insofar as it is a “form of ideal, [a] sum of representations linked to the idea of performance (economic, social, sexual and bodily)”, should not be conceived as a male monopoly, although the incarnations of hegemonic masculinity attempt to essentialise it for their own benefit. This virility is, however, only one attribute among others of a form of masculinity that is enriched by characteristics related to social class, ethnic origin and sexuality.7 Also, this hegemony in which aviators participate does not prevent it from being contested or put into competition, particularly by women who could take over the virile codes and redefine the contours of masculinity. It therefore seems essential not to exclude women aviators from this study, in order to obtain as complete a picture as possible.

This article focuses on common representations without neglecting social interactions and including nuances necessary for in-between situations. Indeed, “the aviator” and “the aviatrix”, like “the man” and “the woman”, are social constructs that tend to polarise and smooth out the multiple experiences of men and women.8 Gender as well as the injunctions and stereotypes associated with it are in fact less obviously established than the social construction of “masculinity” and “femininity”. Their status is relatively unstable and depends on the socio-cultural context in which they are embedded.9 Spaces for emancipation from the dominant masculinity are thus more or less open depending on the country and the time. Taking into account national frameworks allows for a better understanding of social relations as well as aeronautical relations, i.e. the social spaces in which gender is inscribed.

Germany and France allow for comparison between a country that has remained democratic and another that has gone from Empire to parliamentary republic and then to Nazi dictatorship, whose relationship to aviation and to gender was different from the rest of Europe. As neighbouring and antagonistic countries, they were in constant contact and shared experiences, notably that of the Great War, whose effects on society can thus be compared. This shall help to identify constants and/or divergences until 1939, that is, when the Second World War reconfigured gendered identities through the remobilisation of individuals, the mutilation of bodies, and the trauma of psyches. Moreover, linking French historiography, which has focused particularly on the figure of the pioneer airman, to German historiography, which has worked more on the figure of the female aviator, will be instrumental to determine to what extent aeronautical culture was part of a masculine culture in the first part of the 20th century. In other words, did Saint-Exupéry’s Terre des hommes (Wind, Sand and Stars), which exalted camaraderie between aviators as well as humanism, left a place in the sky for “women of the air“?10

This article does not claim to be exhaustive and offers perspectives for further research. It takes as its starting point the establishment of the first representations of the aviator, which were – although uncertain – already mainly masculine. These virile bases formed an initial dominant representation of the aviator before the experience of the First World War transformed it. The article will then analyse the impact of the militarisation of the wartime aviator and the transfer of these representations to civil aviation in the 1920s. This second phase corresponded to the appropriation of professional aviation and its institutions by men in an exclusive way, because aviation was (also) a weapon and women were not allowed to handle it. Some women nevertheless managed to make their way in the aeronautical world, especially at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s. Therefore, this article will finally examine in greater dept the evolution of women’s place in the increasingly masculine aeronautical world during the inter-war period. Their exceptional status and their image as “new women” allowed them to use aviation as a means of relative emancipation before the rise of Nazism and the military preparation for the Second World War strengthened the male hold on aviation. This pathway shows how aviation was developed and reinforced as a gendered space. It reveals how the aviator has increasingly become an artefact of hegemonic masculinity in Germany and France, despite the attempts of some women to navigate this male-dominated space in a fundamentally unequal gender relationship.

1. The aviator, a figure of hegemonic masculinity in the first half of the 20th century

1. 1. Air as a new frontier: masculinity validated by confronting the dangers of the unknown

As a new figure emerging at the beginning of the 20th century and because they were mainly men exposed to the gaze of their contemporaries, aviators incorporated a number of representations that had previously belonged to other incarnations of hegemonic masculinity. As David Courtwright has explained, aviation in its early years used a vocabulary that had already been employed in the nineteenth century: envisioning the sky as a frontier, aviators were pioneers who participated in its conquest.11 The air, a relatively unknown space symbolically reserved for the gods since Antiquity, was now open to man. Seen as a flying avant-garde, the aeronauts of the end of the century were distinguished from the common man by their physical and symbolic elevation in relation to the rest of humanity, riveted to the ground.12 By entering the third dimension by means of light constructions of wood and canvas equipped with engines, the aviators followed in their footsteps in the second half of the 1900s, at a time when aerial exhibitions were developing. Gabriele d’Annunzio, after attending the Brescia airshow in September 1909, was particularly instrumental in assimilating the aeroplane pilot to a superman. Confronted with flight, in full light and glory despite the danger and the possibility of violent death, the aviator on his frail aircraft would thus have appeared as a sort of demigod reminiscent of the mythical figure of Icarus.13

Aviation was a mechanical sport that was offered as a spectacle, with some of the European elite attempting to beat previous records, but also competing against each other and playing with death at international meetings. It thus became a particularly favourable ground for the (re)construction of a hegemonic masculinity at the beginning of the century.14 The first active aviators in Germany and France were overwhelmingly white men from the petty and middle bourgeoisie, or even the nobility.15 Their financial means were sufficient to enable them to create or buy aeroplanes and to train in their use on the outskirts of urban centres. Fairly young in view of the efforts to be made and the novelty of the technology to be mastered, and well dressed, they also displayed a certain nonchalance in the face of the risks involved and thus developed the image of the ‘dandy’ aviator, living in relative carefree fashion, as can be seen, for example, in the memoirs of Roland Garros.16 In contrast, as we will see, the few women who took the controls of these motorised devices before 1914 were judged ambivalently by their contemporaries, who were unsure of how to position themselves in relation to these sportswomen who joined the male effort.17

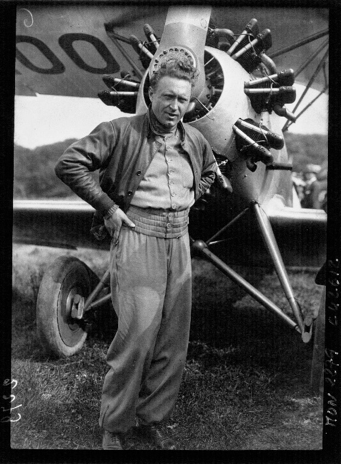

The frequent confrontations with danger, which involved the deployment of strength and physical feats at the controls of the aircraft, were indeed all validating experiences of masculinity for these elites, in a context of the physical and symbolic construction of sports by men, partly in reaction to what was identified as a contemporary crisis of masculinity.18 In German iconography, for example, attention seems to have been focused more on the bodies of aviators and the strength they conveyed than in France, as suggested by the poster for the Konstanz seaplane meeting in 1913. Occupying the whole poster, the aviator wearing boots, a flying suit, a helmet and a thick scarf was portrayed facing the viewer, his legs spread and firmly anchored in the ground, his left fist clenched and pressed against his hip. He gives an impression of strength that is reinforced by the severe traits of his face, turned towards the right of the poster, i.e. towards the future. His right hand holds a seaplane like a plate, symbolising the perfect mastery of the machine by this man.19 This artist’s vision of the aviator par excellence finds other echoes in popular culture and the arts.20 It seems to reflect a hexis, a body posture and an overall appearance specific to aviators that accentuates their virile character, particularly through the manifestation of physical strength.21 This remains visible in many wartime photographs, whether of a German pilot held prisoner, of the famous ace Oswald Boelcke posing with his British prisoner Robert Wilson and adopting the same posture, or of the other famous pilot officers Eduard Schleich and Hermann Goering.22 This portrayal of the German aviator seems to be independent of the gender at that time, as the Fräulein Flieger (“Miss Airman”) was also photographed by the famous Berlin postcard studio Sanke in aviator’s outfits and in this same posture23. However, she preserved the characteristics conventionally associated with femininity: high heels, hands on hips, face open with a smile. Gerhard Fieseler, a former war pilot, still poses more or less the same way in front of his plane but without a uniform in 1932, showing the relative persistence of this stance24. In France, most of airmen’s portrayals had less forceful features: the legs were usually together, the hands in the pockets or behind the back. It was not until the end of the 1920s that postures comparable to those of the Germans were observed in Jean Mermoz, a relatively unique “kind of Tarzan of the airs”25 – perhaps as a result of more direct and numerous contacts between French and German aviators.

Fig. 1. Bodensee-Wasserflug 1913

“Bodensee-Wasserflug 1913”, reproduced in facsimile in Plakat gedanke und kunst (Stuttgart: Propaganda Stuttgart, 1912), 20, https://jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.29391751.

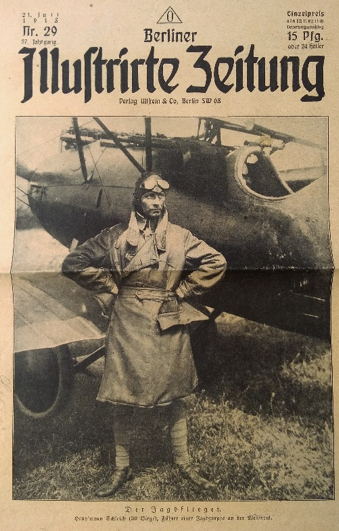

Fig. 2. Eduard Schleich

Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Kriegsarchiv, Munich, MMJO V K 18/12, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 21 July 1918.

Fig. 3. German Postcard “Fräulein Flieger”

Personnal collection of the author, Postkartenvertrieb Willi Sanke, “Fräulein Flieger”, 5000/3, Berlin, ca.1918.

Fig. 4. Gerhard Fieseler

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Mondial, 2279, The German Fieseler, 4 June 1932, http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41599162b.

1. 2. Heroic masculinity or the praise of mastery

René Schilling and Marionne Cronin applied the concept of heroic masculinity to analyse the heroisation of aviators, insofar as these few men became, in the first part of the 20th century, models who participated in the hegemonic masculinity.26 This heroism was characterised in particular by the control these men kept, even in the most precarious circumstances. Their practice of flying, a delicate exercise inaccessible to most other individuals, placed them in a position of superiority while making them exemplary. In line with the nuances introduced by Demetrakis Demetriou regarding hegemonic masculinity, aviators thus manifested both internal hegemony – over other men – and external hegemony – over women.27

The success of the aviator’s flight reflected – in the idea that their contemporaries had of it – the relative mastery over their environment (air, bad weather), the laws of physics (gravity, weight) and the natural obstacles (mountains, seas and oceans) that pilots progressively “erased”. For a predominantly male intellectual bourgeoisie, the elevation of heavier-than-air aircraft was sometimes interpreted as the triumph of the spirit and the human will over matter, but also as the domination by human beings of “Mother Nature” (Mère Nature) in the French case, or “Mother Earth” (die Mutter Erde) in the German one28. The femininity granted to nature and the earth thus contrasted with the altitude that the pilot took to overlook the world from which he seemed to be extracting himself. Rising above the masses, he distinguished himself from them both physically and symbolically, as women began to access leisure activities formerly reserved solely for the male elite. In this respect, aviation was part of a movement analogous to mountaineering in Germany and France.29 As an “old and lonely mountaineer”, the pilot Erwin Böhme himself drew this comparison:

The new mastery of the air resembles the conquest of the Alpine peaks in that it also leads into the realm of the air, which is inaccessible to the masses…] it was a much nobler feeling of victory to have conquered all difficulty and danger with my own strength alone. As an old alpine ‘soloist’, I was already predestined for fighter flying.30

The air and the mountains, seemingly preserved from the imprint of civilisation, thus appeared to be virgin spaces that enabled the individual to be purified and morally regenerated.31

The heroic aviator thus seemed to dominate his environment by the strength of his own body, both physically and spiritually. This was a standard feature in the sport as it developed at the end of the 19th century, which, attached particular significance in the case of aviation to the control of the nerves (Nerven). The Prussian physical culture prior to 1914, which emphasised stoicism and self-control, thus pervaded the medical examination of aviators. Indeed, although very efficient for their time, the first devices were rather rudimentary. Only the possession of “healthy” and solid nerves would enable one to respond effectively to the performance of the machine, to contain and control it32. To this extent, the self-control of the aviator also conditioned the control of the machine. This led individuals to overdetermine the importance of the mind in aerial success. A man would have an “aviator’s mind” provided he had sufficient moral strength, which would allow him to always dominate the sometimes-failing technology, contributing to thinking of the air as a world reserved for the strongest souls.33 This made the few female aviators all the more remarkable, as we shall see.

1. 3. From phallus to joystick: regeneration and power

Perhaps even more so than aeronauts, who benefited from the lightness of gas to rise into the air but appeared relatively passive in the ascent, aviators established themselves as models of heroic masculinity insofar as they would actively participate in lifting heavier-than-air machines by means of the powerful engines they piloted. Thus, the aeroplane was sometimes assimilated in turn-of-the-century literature to a vitalist and eroticised symbol, notably through the metaphor of ascent, which refered the ascent to erection or the union of man and the cosmos to coitus in the work of an author such as Stefan Zweig.34 The relationship between modern man and his machine can therefore be understood as eroticised on a symbolic level, particularly through the appreciation of the machine as an extension of the male body with a phallic dimension.

The equestrian culture of the European elites, which partly based the “survival of heroism” in the 19th century on the “cavalier ideal” and “the quest for aristocratic honour that it conveys”, often led the actors to compare the plane to a mechanical horse.35 The handling of the most modern aircrafts, which were particularly fast and therefore dangerous, thus appeared as a performance of masculinity, a marker of power. Pierre de Fleurieu recounted having had, as he took the commands of a Nieuport for the first time, “the impression never experienced since of being astride a shell. But at last I managed to dominate this fiery mount […] and returned triumphantly to the hangar with my tail held high as it should be”.36 Like the steering system – the “joystick” – placed between the pilot’s legs, the fuselage itself seemed to be associated with the phallus to the point of forming an extension of the individual. Erwin Böhme confirmed this impression of a pilot merging with his machine:

You no longer have the feeling that you are sitting in an airplane and steering it, but it is as if there is a spiritual contact. It’s like a good rider who […] is so completely at one with his horse that the horse immediately feels what his rider wants. Both have full understanding and trust in each other, and it is a will that animates them.37

The pilot had to climb onto the aircraft to enter it, take control of it and fly away. In a sense, he was one with the machine, which “augmented” him, both in his performance and in the masculinity that results from it: more powerful, the futuristic “machine-man” would only be more virile. For a poet such as Walter Hasenclever, describing his first flight over Leipzig and exclaiming: “Man of flesh – You have become steel!”38 The symbiosis of man and machine thus led Fernando Esposito to analyse the aviator as a “mechano-organic hermaphrodite” (mechanisch-organischer Hermaphrodit), whose sex was indeterminate for his observers when he was in flight.39 Indeed, this erotic relationship between the aviator and his mount was probably not foreign to the few female aviators, who could also take the upper hand over the machine before 1914, but sources are lacking to provide a substantiated answer to the question.

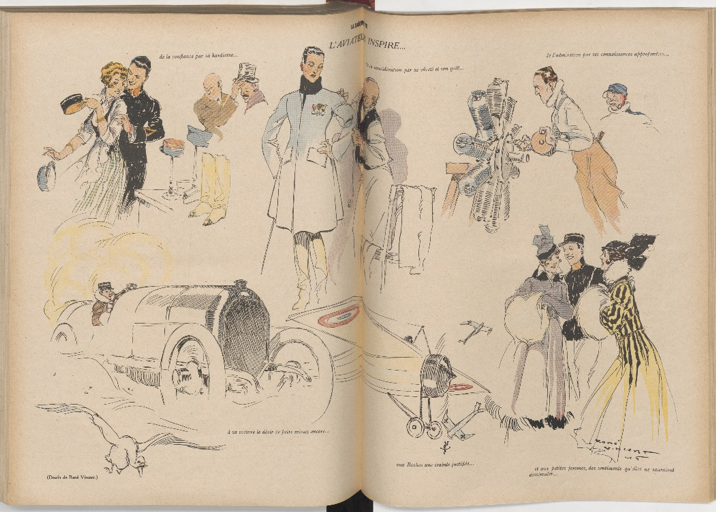

However, the dominant representations of the aviator clearly fall within a heterosexual framework. The desirability of flight and risk-taking was closely associated with the masculine and the materiality of the ground and safety with the feminine. Daniel Berthelot, President of the Société Française de Navigation aérienne, explained for example at the beginning of 1914 that “women were appalled by aviation. The men who had begun the noble and dangerous apprenticeship saw before them the grieving herd of their mothers, their sisters, their mistresses.”40 The gender injunctions were reinforced by such narration of these charming pilots, who nevertheless did not speak about their relationships to their contemporaries. This was probably more evident in France than in Germany, where officers’ representations tended to give precedence to morality and a sense of duty over any carnal relationship before the end of the 1920s.41 Thus, René Vincent was able to portray the French aviator as elegant, bold and desired by women in the pages of the wartime newspaper La Baïonnette at the end of 1915, aimed at a largely male readership. The aviator was thus a social referent among other figures of a hegemonic masculinity with which men were required to identify. This seems to have worked, since in matrimonial advertisements, some of the men who wished to appear virile portrayed themselves as aviators, much more regularly than the women themselves claimed to wish to meet a pilot.42 This gendered division seems to be rooted in aviation culture. Olivier Odaert considers that in French aviation novels of the early 1920s,

according to a pattern that has gradually become traditional, or at least received as such, the symbol of the aeroplane concentrates […] a system of virile and solar values which are opposed by the temptations of the always deceitful and carnal female relationships, dangerous mistresses often linked to the moon.43

Thus, the aviator was modelled as a free and vitalist male figure, escaping through his vigourous personality from the material contingencies and baseness of the world.

Fig. 5. The aviator portrayed by René Vincent in late 1915

R. Vincent, “L’Aviateur inspire…”, La Baïonnette, 23 (16 December 1915), 376-377, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6580711t/f8

2. From war pilots to airline pilots: strengthening the masculinity of the sky

2. 1. The sky of war, a sky of men by excluding women

The Great War was the first to involve airmen in a strategic and massive way in armed operations. The conversion of the “peace aviator” (Friedensflieger) into a “war aviator” (Kampfflieger) was all the easier as some of the values attributed to civilian pilots (endurance, tenacity, self-sacrifice, strength) were also militarised manly values, and some of the aviators were already employed by the army before the war.44 The spread of the Prussian model of compulsory service in France, as in Belgium and Italy, had in fact helped to reinforce a virility militarised by the barracks.45 The army had become a bastion for the preservation and reproduction of masculinity during the 19th century, while a certain number of women were gradually escaping gender injunctions and appeared to threaten the foundations of male society.46 In this perspective, the Great War reinforced gender stereotypes in the long term as it allowed men to make legitimate use of violence while women were excluded from bearing arms and were relegated to a situation of dependence.47

This phenomenon of crowding out is very clear in aviation, as some forty women had already been licensed as pilots of civilian aircraft before August 1914. There were six German women out of the 800 or so aviators in Germany, and eight French women out of 966 male pilots.48 As rare as they were, these women were excluded from flying in both countries. Overall, no women took up arms for the air forces on the Western Front.49 Offering her services to the French army for the first time in October 1914, the aviatrix Elisa Deroche was rejected each time she and her colleagues in the Union patriotique des aviatrices de France (Patriotic Union of Women Aviators of France) made a request from April 1915.50 The latter again complained, without success, in an article in the Figaro in September 1915: “Aviators are very well received everywhere. Why push back the women aviators? […] we do not pretend to bomb cities. Leave us behind, like Red Cross ladies, and make us work there.”51 Aware of the social framework in which they were embedded, women aviators claimed – but did not obtain – the use of aviation to carry out tasks traditionally assigned to women, such as caretaking and maintaining the home front. In the same way, in Germany, women aviators had to stop their activities, like Melli Besse, the first German woman to obtain a pilot license in 1911. A flight instructor and an aviator, she was forced to stop her activities, especially as her husband, Charles Boutard, was French.52

The gendered division of European societies at the beginning of the 20th century thus extended to aviation the “group portrait without a lady” that war became when it was conducted and narrated by men.53 A pilot such as Ernst Udet could thus describe the world of military aviation as a world that no woman could understand.54 The male appropriation of the airspace became such that, on the German side, the homosocial relationship between a pilot and his observer was described as an “aviators’ marriage” (Fliegerehe). Although a female aviator such as Marie Marvingt was described after the war as having taken part in two bombing missions in 1914, there is no evidence to support this claim and it is difficult to determine whether this narrative was not an ex-post construction of a heroic female figure at the end of the war.55 In a reinforced masculine universe and the according narrative, women seemed to be reduced to the rank of substitutable commodities, one-night stands or mothers who were recipients of stories, even though there are evidences of serious sentimental bonds for many airmen during the war years.56 The armed aircraft was henceforth vested with a stronger virile charge, as shown by the portraits of airmen posing most of the time in front of the plane or at its commands. The machine gun that equiped it symbolised even more obviously the male sex in erection when it was straddled, as did the officer-observer of the pilot Louis Coudouret in the loose context of his personal album in autumn 1915.57

Fig. 6. Photograph from the album of Louis Coudouret, a bombing pilot with VB.102, 30 September 1915

Archives départementales de l’Hérault, 1J310 (view 44), Coudouret collection, photo of Lieutenant-Observer Prodolliet and pilot-aviator Louis Coudouret, Malzéville, 30 September 1915, https://archives-pierresvives.herault.fr/ark:/37279/vta0f983a1c83484480/daogrp/0/44.

2. 2. Gradients of masculinities, from “Knights of the air” to deviralised bombers

This male sky reconfigured in wartime transformed representations of aviation in Germany and France in varying ways. Joëlle Beurier’s work has established the clear difference between French illustrated magazines, which attempted to show the war as close to reality as possible, and German illustrated magazines, which attempted to soften the front and its violence. French newspapers increasingly emphasised soldiers as ‘everyday heroes’ facing the difficulties of war, while in Germany the virile characteristics of the male hero were reaffirmed and accentuated to the point of turning the modern German soldier into a super ‘man-machine’, resisting and fulfilling his duty until victory.58 Thus, from 1916 onwards, German illustrated magazines focused on young combatants, handling and magnifying modern technology.59 In both countries, the young and athletic bodies of daring and machine-taming airmen were all the more prominent as the majority of combatants found themselves buried in the trenches, relatively powerless in the face of mass death.60 Deviations from these dominant models of masculinity tended to be erased: Max Immelmann’s coquettishness was removed from his published correspondence while Jean Navarre’s loss of mental capacity was mitigated by censorship.61

Allowing, on the contrary, to re-establish a sort of rationality in the industrial mass warfare, there were numerous references that inscribed aviation in a rich and deep warrior genealogy going back to ancient and medieval times. The analogy between the horse and the plane, as well as the imaginary of the aerial war – supposedly fought through aerial jousts – progressively forged the success of the chivalric metaphor, which became popular in France in particular from 1917 onwards in the tributes to the deceased Georges Guynemer.62 The success of medievalism in the 19th century have probably favoured the development of this representation of a gentlemanly war above impersonal slaughter, which preserved the virile rhetoric of honour, courage and fair combat.63 The same analogy can be found in the memoirs of the German pilot Carl Degelow:

Aerial combat was comparable to the medieval tournament in which the opponents fought openly and freely. […] one did not fight against an invisible enemy, but saw one’s opponent, armed only with his goggles, freely and openly in front of one. These conditions of combat, which rarely occur in field warfare, provoked […] a certain chivalry.64

The imaginary of close combat, of the duel between two alter-egos fighting each other on equal terms, thus made it possible to maintain the fiction of a cleaner chivalrous war in the air. It seemed to reenact the bourgeois duels which, like the aviation of the pioneers, based masculinity on individuality and mastery, both of the weapon and of the body.65

This figure of hegemonic masculinity, which the fighter pilot became, captured the media’s attention from 1916 onwards. It stood up to other types of masculinity, notably the more negative one that bombers seemed to display.66 Their virility was sometimes questioned as their actions were devalorised or rejected. They were not considered as “real men”, i.e. real fighters: they appeared as cowards, well protected from the air, and would deviate from the chivalric creed to bomb defenseless civilians and children. This negative masculinity of airborne bombers was particularly evident in an author such as Jean Bastia, who wrote a “Zeppelinade” in early 1915 in which he compared the aircraft to a “large phallus violating the virginity of the stars,” a “demon” scattering “sterile seeds” to “depopulate the world”.67 However, this representation was essentially applied to enemy airmen through their aircraft, by metonymy. In the case of the Allied airmen, on the other hand, the heroisation was certainly less strong yet real: the military necessity justified the self-sacrifice and the accomplishment of their duty by these bomber airmen, like on the French side the bomber aviator Henri de Kérillis described by La Guerre aérienne illustrée, or on the German side the Zeppelin captain Peter Strasser and the bomber pilot Hermann Köhl who both received the prestigious Prussian order Pour-le-Mérite and were therefore recognized as exemplary.68 Thus, gradients of masculinities could be observed in the representations of aviators depending on the significance that contemporaries gave to their actions. The air fighter was a model of masculinity insofar as his combat remained confined to military airspace and respected its militarised virile principles. The bomber was a more ambivalent figure and certainly lower on the scale of values. He appeared nonetheless higher than the ground staff, or even the members of the sanitary air force that was developed during the interwar period and less directly involved in the fighting. This shows the symbolic importance of the plane as weapon and its uses by airmen from the Great War onwards.

2. 3. Civil aviation, the manly adventure of modern men

The aviator thus emerged from the Great War virilised, while he took the controls of civilian aircraft, setting off on new epics. While European societies were measuring the horror of trench warfare, the ability to master one’s destiny and the mystique of flying were exalted more than ever.69 Ernst Jünger could state that “the flying man is perhaps the sharpest expression of a new masculinity. He represents a type already foreshadowed in the war.”70 After the “aces”, exemplary and heroic soldiers, the first airline pilots were true adventurers because their only mission was to transport mail, a ridiculous goal in comparison to the dangers they faced. Joseph Kessel, himself a former wartime pilot, summed up this continuity in 1933 when he said that “the adventures of the air are the supreme chanson de geste of our time.”71 Like the European explorers of the 19th century, the aviator was part of a set of prescriptive and formative masculine representations. The hardships and physical risks taken became a means of restoring the value and intensity of human life in a disenchanted modern society. They were nostalgic embodiments of an evanescent world that technical progress was trying to render obsolete by automating it and making it safe. In Germany as in France, aviators such as Ernst Udet, T.E. Lawrence and Jean Mermoz were all popular heroes who animated this aerial adventure.72 Their media coverage made them modern standard-bearers, “ambassadors of the air”, while the imperial dimension of aeronautics was asserting itself. After the Great War, the control of airspace as well as of advanced technologies seemed decisive. Flying over many territories, the aviator embodied the power of his nation. Several authors tried to place the airlines' actors in the lineage of the aces of war, contributing to the heroisation, particularly in France, of the pilots of the air mail lines.73 Referring to the pilots of the Aéropostale company, Jean-Gérard Fleury stated that “through them, the Latin American nations know that there are still Knights in France.”74

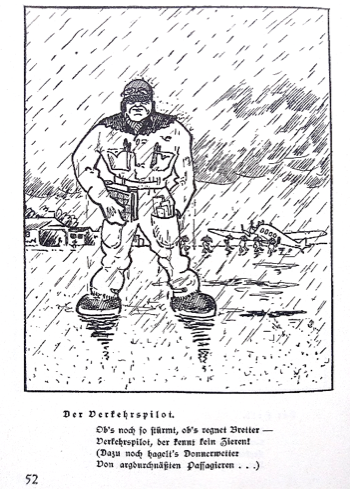

As technical as it was strategic, and therefore perceived as rewarding and desirable in the 1920s and 1930s, the profession of aviator became a “man’s job” par excellence.75 While it is true that significant physical strength was required to maneuver increasingly heavy transport aircraft before the introduction of servocontrols, the argument was not explicitly put forward in the inter-war period.76 In the post-war context, when European economies were undergoing conversion and the new commercial aviation was flourishing, jobs were relatively scarce and sought after by more numerous aviators who had been trained with government subsidies. After several years of armed conflict, they were more experienced and better trained in flying several types of aircraft than the women who were deprived of flying.77 The bonds of camaraderie forged in the squadron also favoured endogamous recruitment which, coupled with the pilot habitus, excluded women from the airlines. This led for example Ernst Udet to portray the transport pilot as a muscular man unafraid of bad weather and ready to brave all circumstances to accomplish his mission. Perfectly equipped and a master of modern techniques, he embodied the adventurers of the air celebrated in France by Joseph Kessel,

those same flying men and their comrades, whom their passion and their duty unite in a fraternal heroism […]. From Toulouse to Santiago de Chile, along this line of fierce struggle and stubborn hope, it carried with them the mail for which they risked their generous lives.78

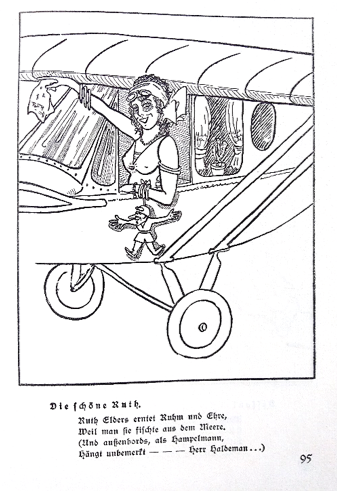

In contrast, in Udet’s same album, the only female aviator depicted, Ruth Elder, was portrayed as a scantily clad woman, wearing make-up and smiling from the window of her aircraft, winking at the onlookers whose attention she attracted with her embroidered handkerchief.79 This is an indication, if not of a certain machismo, at least of a gendered division of the air, referring men and women to their assigned social status.80 This vision fitted quite well in the Nazi line, of which Udet became one of the main protagonists from the mid-1930s onwards.

Fig. 7 and 8: Caricatures of a transport pilot and the American aviatrix Ruth Elder drawn by the German aviator Ernst Udet in 1928

Ernst Udet and Karl C. Roellinghoff, Hals- und Beinbruch. 100 lustige Karikaturen (Berlin, 1928), 52 & 95.

Indeed, women’s unequal access to aviation was reinforced in the 1920s. While men could benefit from free flying instruction as part of their military service, women who wished to fly had to pay for private lessons and/or acquire second-rate aircraft, such as the decommissioned Caudron that Adrienne Bolland had to use for her flight across the Andes.81 Similarly, in the context of the ban on German military aviation, the Deutsche Luftfahrtverband (DLV) only subsidised flight training for men, with a view to building up a reserve of potential military aviators. Thus, although women were allowed to train as pilots at the end of the 1920s, their training was de facto more expensive because it was never subsidized.82 Moreover, it could only concern sport and aerobatic piloting, since the International Commission for Air Navigation (ICAN) made “be[ing] of male sex” a “medical requirement […] before obtaining a licence as a pilot, navigator, engineer, or member of the operating crew of aircraft engaged in public transport” from 1924 onwards.83 Thus, civil airspace became an exclusively male sector in view of the physical and emotional instability allegedly inherent in women nature.84 Indeed, the medical criteria used by several experts to qualify the best pilots – “nerves of steel”, self-control, courage, decision-making ability – were essentialized as masculine. They thus made the “aviator spirit” a “naturally” male quality, which characterised professional pilots.85 Excluded from commercial aviation, women rarely had the opportunity to compete with men in sport aviation, especially in the quest for speed records – the most spectacular and prized ones – which were only accessible on condition of having the most powerful aircraft, which were still allocated primarily to the most experienced pilots, i.e. to men.86 As a result of these various obstacles, although sports aviation – like tennis – allowed some women to make a name for themselves, aviatrixes were extremely rare compared to aviators before 1939. While the United States was the exception, with more than 500 female licensed pilots out of some 18,000 in the early 1930s, there were around 200 in the United Kingdom, 50 to 60 in Germany and barely 40 in the French empire as a whole.87 It is therefore important not to be fooled by the mythical narrative of exceptional female pilots’ careers, which would be part of a progressive and global emancipation: hegemonic masculinity is also defined by the imposition of power over women, which can be observed in the aeronautics during the interwar.88

3. Women aviators “in the negative”: the history of the sky in unequal parts

3. 1. Female aviators, virile women?

Masculinities are part of a dynamic system of relationships in which men and women lead gendered lives.89 Women pilots also position themselves in this universe in relation to men and their appropriation of masculinity. Always perceived through the prism of their femininity and compared to men because they were women pilots, women aviators performed in a virile manner and were also invested with characters considered by their contemporaries as masculine. While their transgression of gender injunctions could be seen as a “feminine masculinity” as proposed by Thierry Terret90, one could consider it rather as the performance of a virile femininity, i.e. a femininity that appropriates and integrates virile elements before the eyes of men. Talking about virile femininity would therefore help to clarify Judith Halberstam’s concept of “female masculinity” – a masculinity which is autonomous from men themselves – because it is in fact a virility – a set of invariant and positive attributes related to performance – that these women have come to contest from the male monopoly by transgressing the roles they had been assigned by hegemonic masculinity.91

At the beginning of the century, the sports press, which echoed representations of dominant masculinity, was puzzled on the subject of the first “women of the air” between a condescending conservatism and the recognition of exceptional women.92 The athletic dimension of aviation meant that, as with men, biographers emphasised the multidisciplinarity and taste for physical effort of female aviators93. The first female pilots, Elisa Deroche (8 March 1910 in France) and Melli Besse (13 September 1911 in Germany), were depicted in relatively similar fashions to their male counterparts, at the controls or in front of their aircraft.94 However, their outfits differed – skirts, woollen jumpers or fur coats – while the suits were not yet standardised. The war, which deprived them of flying, kept them away from the airfield for a long time. It made them invisible and/or forced them to confine themselves to a “female” commitment, such as caring for the wounded. The second generation of female aviators who emerged from the mid-1920s onwards reflected a more gendered relationship with these women, who became the embodiment of the “new woman” – “femme nouvelle” or “Neue Frau” – whose modernity was also expressed in the new, more androgynous hair and clothing fashions that were available to young women.95 In France, this new woman was also known as the “garçonne”, a social (stereo-)type that catalysed the anxieties of French (male-dominated) society in the 1920s and 1930s.96 Not coincidentally, the writer Victor Margueritte, who helped to popularise this figure with his scandalous novel La Garçonne (1922), evokes in Nos égales (1933) a young woman of 19 who told her parents that she aspired to become an aviatrix, like the girls of her age whom she saw in the aeronautical newspaper Les Ailes.97 The figure of the aviatrix, so associated with modernity, seemed to be so avant-garde and a harbinger of future times in Germany that the “new human being” (der neue Mensch) depicted on the cover of the illustrated weekly Die Woche was a woman in flight suit on 29 January 192798.

The short hair and the standardisation of aviation suits were in line with the undifferentiation of appearances, whatever the gender. With her boyish haircut, Adrienne Bolland “dressed in her pilot’s suit, […] looked like a young mechanic”, says journalist Louise Faure-Favier, before adding that “she is an excellent pilot” – always in the masculine form.99 Helmets, glasses, overalls, boots, trousers and large coats erased the forms and standards of femininity: long hair, pumps, dresses and thin fabrics that revealed the lines of a body that was at least partially corseted. The delicacy assumed for women was no longer immediately apparent in their silhouettes when they flew.100 Such was the gender confusion that after a flight for Lufthansa, the co-pilot Marga von Etzdorf – who had not been recognised as a woman – greeted her passengers in return “with a silent, manly bow”, leaving nothing to be guessed of her identity.101 According to Guillaume de Syon, the aviation suit had the advantage of not revealing too much of the female body, underlining a quality perceived as feminine – discretion – before returning to their feminine finery outside the airfield.102 A “feminine wearing” of the belt – at waist level rather than at the hips like their male counterparts – nevertheless suggested the curvature of the admittedly decorated bodies and, along with the face, betrayed the biological sex alone. Marie-Claire emphasised at the end of 1938 this contrast that “under the heavy, masculine uniform, it is nevertheless a clear, fresh face of a young girl that one finds”.103

The difficulty that literary men had in positioning themselves in relation to these modern women led them to mobilise previously established cultural referents, in particular to turn them into Amazons.104 Carl Maria Holzapfel described the transformation of German women aviators, driven by the rhythm of time (Rythmus der Zeit) and the rhythm of the engine (Rythmus des Motors), into Amazons of the air (Amazonen der Luft).105 Liesel Bach was upset by the labels of “tomboy” (Mannweibtyp) and “Amazon”, which reduced her to being, in her opinion, only half of an individual and not a full woman.106 However, according to Erik Jensen, this reference to Amazons allowed for the integration of the equal status of men and women in the modern era while implicitly suggesting the bellicose challenge to male pre-eminence.107 This was illustrated when Joseph Kessel’s magazine Confessions described Maryse Bastié as a “heroic Amazon of the air […] revolting against the tutelage of her family” at the age of ten, before she herself told the reader that “it was my first marriage which, breaking down what I was too fiery, too straightforward, first made me fit for happiness.”108 The balance was thus struck between the contestation of gender hierarchies and the return to order through the marital alliance. The latter was regularly questioned by journalists who were probably anxious to know when the celibacy of these young women would end, especially in France where the declining birth rate was a constant issue during the interwar.109 The possible homosexuality of these “Amazons” was never mentioned, however, even implicitly. While the multi-sporting Marie Marvingt was promoted as the “bride of danger” (fiancée du danger), promised to adventure in a metaphor useful to the aerial narrative in the 1910s, the risks incurred by female aviators in the air seemed to make their contemporaries fear that they could not assume the status of wife and mother that was assigned to them in the long term. The Countess of Mantigny thought it useful to point out in Les Ailes that “aviator husbands can rest assured that the majority of French women who love and practice flying will increasingly be their companions, but not their competitors.”110 It is unclear whether her plea was heard.

Women aviators played anyway on these different registers of curiosity and anxiety to distinguish themselves and fit into a world shaped by and for men, without fundamentally questioning its foundations. The coincidence of the development of aeronautics with that of celebrity culture allowed media attention to be focused – relatively disproportionately in comparison to their numbers – on these original and heterodox young women.111 As Siân Reynolds pointed out:

Most women pilots remained loners, then, strange glamorous figures whose relationship with the rest of the world was conducted through the media. As a result, they actually reinforced images of femininity more than they challenged them.112

Adrienne Bolland was indeed “charmingly graceful and carefree” for Le Figaro while Les Ailes painted “a delicate portrait” of the “charming aviatrix” Maryse Bastié.113 The surpassing of oneself and the effort being in opposition to the moderation and the measure of gestures – injunction set to the female gender – these women had to make their practice of sports acceptable by returning to more “feminine” attitudes outside the airfields in order to prevent a too strong transgression.114 If the suits hid the clothes and the bodies, these were exposed again as soon as they got off the plane: the appearance of these women was all the more scrutinised as they were celebrities whose sulphurous character was likely to attract attention. Adrienne Bolland, Hélène Boucher and Maryse Bastié took part in the launch of Caron’s perfume En Avion (1930) dedicated to female aviators, while modern women were enjoined to wear make-up that could withstand the speed of the plane.115 In the same vein, the couturier Jean Patou, who contributed to the spread of sportswear fashion in high society, emphasising the shape of the female body through the use of supple materials, dressed, among others, female aviators in the 1920s.116 Commenting on one of his latest creations with a “completely masculine” jacket, the monthly magazine Les modes developed: “such is the modern woman, alternatively a lawyer, a star or an aviatrix, more well-groomed and dolled up than she has been in any other era.”117

3. 2. Singular and emancipated? Marginal characters in a gendered universe

Despite this media coverage and their relative fame, few women had a stable income to finance their flights. As they could not legally be licensed to fly commercial airlines, female aviators with permanent jobs in aeronautics can easily be enumerated and remained confined to the margins during the interwar.118 However, they repeatedly demanded, albeit not virulently, to be employed by aircraft manufacturers on a permanent basis, and not just for record-breaking jobs that provided only occasional and precarious income.119 The financial cost of training and then paying for flight expenses (purchase or rental of the aircraft and its maintenance, use of the infrastructure, oil and fuel, etc.), with little prospect of a financial return, limited the practice to a few relatively well-off women in the context of tourist aviation, or even sport aviation.120 “Women’s aviation is currently only a very expensive sport […] and cannot offer the elements of a career. I cannot therefore commit you to building your future on such a project”, replied Marie-Claire – the newspaper for “modern women” – to its young readers at the beginning of 1939.121 If the French association La Stella had federated the women aeronauts of the Aéro-Club de France before 1914, there seems to have been no attempt to extend its efforts after the war.122 They were also kept on the edge of the male social circles that the flying clubs were. Each female aviator therefore remained, in France as in Germany, a singular personality who could only speak for herself. It was only in the autumn of 1939 that Madeleine Charnaux called for the formation of a union of female pilots, who would thus rally behind a collective work, in order to prove the capacity of female aviators to step aside in the media to contribute to the development of civil aviation. Observing the marginality of female pilots of her time, she proposed to go through the margins of aeronautical development, in the colonies, where the major air transport networks were not yet established and where a space would potentially be open to female aviators.123 Nevertheless, this marginal position allows us to revise Joseph Corn and Peter Fritzsche’s analysis that female aviators were used by manufacturers during the interwar to demonstrate the safety of their aircraft and to reassure the general public that the machines were not dangerous. On the contrary, it invites us to insist with Siân Reynolds and Evelyn Zegenhagen-Crellin on the permanence of male domination and the eviction of women from commercial aeronautics.124

The psychologist Elizabeth Baux nevertheless observed, through the desire of female aviators to rise into the air, the absence of an “unconscious brake […] on the expression of their desire to fly with their own wings”.125 The elevation of these pilots would physically translate their will to emancipate themselves and to challenge patriarchal norms, both in the political and military spheres. This could be observed to some extent in France in the second half of the 1930s, during the campaigns for women’s suffrage. In order to attract the attention of the general public, Louise Weiss and the activists of La femme nouvelle brought together the aviatrixes Adrienne Bolland, Maryse Bastié and Hélène Boucher in a meeting at the Alhambra in Bordeaux, and then mobilised the aviatrix Denise Finat to stand as a feminist candidate in the fifth arrondissement of Paris in the 1936 legislative elections. This support was however short-lived. According to Louise Weiss’ testimony, the aircraft manufacturers – all men who produced the airplanes and were the only ones to employ civilian pilots outside of the military and civilian transport – put pressure on the female aviators to dissuade them from pursuing this campaign, at a time when the media played a major role in the funding opportunities available to aviatrixes.126 The social and economic conditions of domination thus forced female aviators to bend to the rules of an aeronautical universe in which every aspect was controlled by men, in terms of infrastructure, financing and the media.

With political equality achieved in Germany since 1919, the majority of German women aviators were not very vindictive despite the relative incrase in autonomy offered to them by media income in the early 1930s. Christl-Marie Schultes was an exception, making very militant statements in favour of women aviators in her magazine Deutsche Flugillustrierte, published from April 1933. Placed in November 1933 under the patronage of Thea Rasche, who had just joined the Nazi party, the magazine was finally banned at the end of March 1935 because it did not conform to Nazi ideology.127 Excluded from the movement of massification and consolidation of aerial camaraderie – the fruit of homosocial relations – women remained confined to the individualism of the beginnings of aviation and the role of singular stars. Their particular demands thus seemed inaudible or out of place at the very moment when the collective dimension of the aerial effort was being strengthened, through the insistence on selflessness, abnegation and sacrifice for the greater cause of aviation.

In the second half of the 1930s, fascist penetration and rising perils made it more necessary to train military airmen as a priority. They actively contributed to re-establishing gender assignments and reinforcing the structurally male character of aviation in both countries. The air training programmes of the Aviation Populaire in France from 1936 and the Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps (NSFK) in Germany from 1937 onwards contributed to a more or less direct eviction of women through the militarisation of aeronautics.128 Women aviators, who until then had been excellent ‘ambassadors of the air’ to convince the world that Nazi Germany was not violating the clauses of the Treaty of Versailles by re-establishing a military air force, thus found themselves reinscribed in gender relations. In the Nazi worldview in particular, ideal women were protective mothers of the Aryan home. They were encouraged to pass on airmindedness to the younger generation, i.e. to train future war pilots but not to set an example.129 The famous Hanna Reitsch and Melitta Schiller were notable exceptions, becoming military engineers and test pilots in the second half of the 1930s. While their rise to the rank of Luftwaffe officer could have challenge the male monopoly on military aviation, their public stances were in the line of increased conservatism and a reinforcement of male hegemony, particularly evident when Schiller finally stated, in a speech she gave in Stockholm in 1943, that “we women aviators are not suffragettes”.130

Conclusion

Dominated, like society, by men before 1914, the sky overhead has become in France and Germany more strongly masculine because of the Great War. After a short period of relative indefiniteness of sky’s gender, the aeroplane turned into a weapon was in the meantime taken out of the hands of women and appropriated exclusively by men, who made it a male monopoly. The mechanical and athletic superman, master of his own destiny, acquired the ability to brutally eliminate his competitors while maintaining a noble and chivalrous appearance. The aviator – and in particular the fighter pilot – became the epitome of hegemonic masculinity in Germany and France.

The socio-economic conditions of domination – institutionalised in the military sphere and then transposed during the interwar to commercial aviation – made it more difficult for women to challenge male domination over the aerial sector. While the relative transgression of gender injunctions by women aviators revealed a desire to break free from female stereotypes and a type of what could be perceived as a “virile femininity” in the air, the transition from an aviation made up of singular figures to a more collective and militarised industry confined these female aviators to remaining exceptions, if not media curiosities, during the interwar. The very large share still held by male pilots nowadays finds clear roots in the period that precedes the Second World War.

This article aimed to open up research perspectives on the embedding of hegemonic masculinity in early twentieth-century aeronautics. The analysis of the permanence and reinforcement of the male hold on aeronautical culture could potentially be refined by the study of influential women in the aeronautical media, such as Louise Faure-Favier or Madeleine Poulaine. Their works and their relations with their male colleagues remain poorly known and could possibly shed more light on their impact on the construction of the aeronautical imagination, while an exhaustive study of French female aviators, comparable to that of Evelyn Zegenhagen-Crellin for Germany, has yet to be written. It is also a stake in the writing of the history of women aviators to unravel the invisibilisation of which they may have been the object, whereas many women were active in war planes during the Second World War.